After my father died, his wife mailed me a box weighing over twenty-five pounds. In the box were seven Bibles. And every page, every verse, every jot and tittle of those books were underlined by pen. This was my father’s final act as dementia slowly peeled away the memories of his wife, his sons, and his identity as a professor, biblical scholar, and missionary. This effort occupied his final three years, the lines in each Bible growing squigglier as Alzheimer’s disease slowly and inexorably turned off the lights.

I loved to watch him doing this: his big fingers, wreathed with veins, tracing the pen across the sacred lines of Scripture; his leathery face peering above the pages like a doctor intent upon his surgery. This devotion to a text he had loved for six decades, a text he had meticulously marked but could now barely understand, puzzled and inspired me.

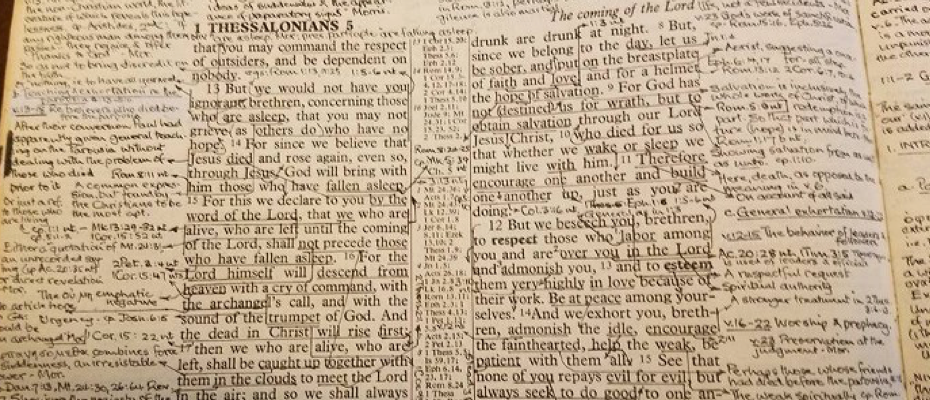

I once hovered over him with my camera, trying to capture something my own eyes might miss. He was the perfect subject, completely unaware of my presence as he placed his ruler over the text and carefully marked it—again and again and again. My father had become like a child, so absorbed in his own world that his only response to my impromptu photo shoot was to ask, “What is that clicking sound?” Watching his face through the camera lens — oblivious and focused, childlike and ancient — brought to mind Psalm 119:83: “I have become like a leather flask in the smoke, but I have not forgotten your statutes” (BCP 1979). This has become for me one of the enduring images of my father, our smoked “leather flask”—doggedly refusing to take the bait of forgetfulness his disease persistently offered him.

***

Two years after he died, I started reading, chronologically, through these seven Bibles, and I began to notice the ways in which Alzheimer’s had affected his marking of each text over the years. Whereas his first Bible was filled with impeccably neat handwritten notes—all interlinked with tiny arrows from his 0.25-millimeter india-ink pen, his second Bible begins to show signs of an encroaching Alzheimer’s: the intricate annotations have been replaced by a simple numerical system that he developed to help his fading memory track what he had just read. For example, in Paul’s final seventeen instructions to the church in Thessalonica (1 Thess. 5:12–22), my father begins circling key words as a simple mnemonic device—something he had not done before—and eschewing the theological commentary seen in his previous Bible.

Then in his next four Bibles the annotations begin to disappear. Instead, he methodically underlines every line of his now large-print Bibles using a pen and a ruler. And in his final Bible, even his ruler has been abandoned: his underlining becomes more and more haphazard—often crashing through the borders between columns, and sometimes continuing on the bottoms of pages, long after the text has concluded.

These extra lines sometimes came in strange places, such as after Paul’s concluding blessing in 1 Thessalonians 5:28: “The grace of our Lord Jesus Christ be with you” (NIV). Paul’s text ends there, but my father’s pen keeps underlining—again and again until the edge of the page. There is something strange about this, as if he were aware that Paul’s concluding blessing was not reaching him. Or perhaps he realized that Paul implied the present continuous tense, as rendered in Young’s Literal Translation: “The grace of our Lord Jesus Christ [is] with you! Amen.” Perhaps he was trying to capture this present continuous tense with his continuous underlining, as if compelling the grace of the Lord Jesus Christ to continue to be with him—line after line after line. I cannot imagine how my father’s final years would have ended without the strange comfort these Bibles brought him. He is like the psalmist who says, “If your law had not been my delight, I would have perished in my affliction” (119:92 ESV). His Bibles anchored him. They became his mentors, his lantern, his comfort, and his conduit to God.

***

The image of my father’s hands doggedly traveling across miles of text blurred by dementia reminds me of C. S. Lewis’s famous sermon “The Weight of Glory,” which he preached during the darkest days of 1941. In that speech, Lewis reminds us that as image bearers of God, we carry a “weight of glory” on our fragile shoulders, and that weight, he says, should revolutionize the way we treat each other: “There are no ordinary people. You have never talked to a mere mortal. Nations, cultures, arts, civilizations — these are mortal and their life is to ours as the life of a gnat. But it is immortals whom we joke with, work with, marry, snub and exploit — immortal horrors or everlasting splendors.”1 But we forget.

This sense of our place in God’s kingdom is easy to forget, but the image of my father as a leather flask in the smoke reminds me again: he carried around on his cracked being a weight of glory too heavy to see, a weight that seems to become more visible in weakness.

For three years I watched him die. I flew out from Kansas to California every three months to be with him, and as I observed his long and painful struggle, I began to see more and more of this strange weight. Some have suggested that Alzheimer’s destroys a person, that it makes its victims stare with blank eyes at a world they no longer recognize. But perhaps our concept of personhood is too infected by René Descartes’s famous declaration that “I think therefore I am” for us to recognize this weight. In Christian ontology, God remembers, therefore I am. And it is God’s memory of us that gives us this weight: “Before I formed you in the womb I knew you, and before you were born I consecrated you” ( Jer. 1:5 ESV).

What I began to see during the last painful years of my father’s life was a fundamental truth about this disease not found in any medical or self-help book on the subject, that Alzheimer’s can be a vivid physical reminder of a far deeper spiritual disease we all wrestle with—a dementia of the soul, a chronic and pervasive forgetfulness of who we are as image bearers of God. This dementia is a deep, ontological forgetfulness that dulls our ability to think beyond what we can see and chokes out our attempts to function as eternal beings.

***

During the later stages of his disease, my father once sternly rebuked his wife, Karen, for trying to get into his bed. “Hey, I’m married, you can’t get into my bed,” he reprimanded her. “Who do you think you are?”

“I’m your wife, Karen,” she would reply, “and this is where I belong.” As sad as this bedtime episode may have been for her, it also provided her with a strange comfort. She came to see that her husband, in his most unguarded moments, was also revealing to her his gift of utter fidelity.

I began to see Karen, this sometime stranger to my father, as the bearer of his fading ontological memories, the bearer of memories about who he was: a husband, a father, a faithful servant of God. She had long ago given up trying to correct his whacked-out sense of geography or time or taste, but she stood guard diligently against the panic created by his fading sense of self. She knew he was still her faithful husband; her resolve helped neutralize his outbursts of anger, violence, and panic toward her. She bore the memory of who he was — present continuous tense!

In his book onthe theologyof dementia,John Swintonwrites compellingly against the common belief that we are the sum of our memories, a belief that suggests that when we remember nothing, we are somehow deprived of our personhood. Swinton argues instead that our value is underwritten by God’s memory of us—not our memory of God. Like Karen, God is the keeper of our memories.2

And this is why David Keckargues that Alzheimer’s is a “theological disease.” It is a disease that reminds us of our spiritual dementia, a dementia in which our identities are rooted in who we are as autonomous beings rather than in “whose we are” as image bearers of God.3 We ask “Who am I?” rather than “Whose am I?” We boast of knowing God rather than of God knowing us. In his letter to the Galatians, Saint Paul corrects this subjective bias by reminding us that “now that you have come to know God, or rather to be known by God, how can you turn back again to the weak and worthless elementary principles of the world?” (4:9).

Two years before my father died, I asked Karen the dreaded questions: When would it all become too much for her? What would be the breaking point? When would she need to give up on her full-time care for him and place him in a retirement home?

She paused before answering: “Two things,” she said. “When he becomes violent toward me, and when he can no longer control his bowels.”

A year later, my father became violent and could no longer control his bowels. Yet with the help of just six hours of weekly hired help, Karen persisted in taking care of him. On my next visit, I asked her why:

“Has he been violent?” She said he had.

“Can he still use the bathroom?” She said he could not.

“Why then have you not put him in a retirement home?” She smiled at the question, knowing that her breaking point had long since passed—and yet I couldn’t help noticing how happy and vibrant she looked compared to a year ago. “He is my husband,” she explained. This was the only excuse she seemed able to muster. She admitted that something supernatural had happened to her. And I saw then the remarkable role she bore as bearer of his memories. He may have forgotten who he was, but just like our heavenly Father, she would not.

Jesus’s most frightening parable highlights this tragic (or willful) tendency to forget: the parable of the unforgiving servant, who, after being forgiven by his master of a debt he could never have paid, immediately goes out and seizes another servant by the throat, threatening to throw him in jail if he does not pay back the small debt owed him (Matt. 18:21–35). We struggle to forgive only because we keep forgetting the immensity of the debt our Lord has paid on our behalf. We struggle with self-image because we keep forgetting who we really are in Christ. And we struggle to love our enemies because we forget that they, too, are created in the image of God — however smudged that image may have become. We keep forgetting, as Keck puts it, “whose we are” (emphasis mine).

This is why neglecting a loved one with Alzheimer’s disease is so tragic. It is easy to feel that because our beloved no longer knows and recognizes us, time spent with them may be wasted. However, even if our beloved can no longer cognitively recognize us, they still retain deep emotional memories of who we are. This has been documented in experiments showing how Alzheimer’s patients still have the capacity to respond emotionally to people and places they may have long forgotten. We can still trigger emotional happiness in a beloved who may no longer remember who we are.4

***

From my father I also learned the way of duty. I learned that nothing meaningful can be achieved without the making of vows. And to this end he lived his life, throwing all he had into planting churches, baptizing hippies in the Indian Ocean, earning two doctoral degrees, and finally, underlining seven Bibles word by word during the final dark decade of his life.

He became a Christian in a South African boarding school at the age of twelve. His conversion occurred after his best friend presented him with a strict code of conductfor followers of Christ. Whereas many would be turned off by such a list, my father was invigorated by it. Duty, not passion, convinced him of truth, and a life without sacrifice and rigor had no appeal to him.

When his second dissertation was accepted at Fuller Theological Seminary in California, we wrote on his cake: “Congratulations Dr. Dr. Paul B. Watney!” And after two decades of planting churches and running a small Bible college in the slums of Cape Town, he sold all his possessions to pay off the debt incurred during his doctoral studies, immigrated to America, and became a professor of theology and missions for the next two decades. Then, at age sixty-five, he began forgetting to return the papers he had graded, forgetting the lectures he had given, and forgetting the names of students he had long known. And very reluctantly, he conceded that he had to do what he always vowed he never would: retire. This development was anathema to my father. He was old-school when it came to work. Like Saint Paul, my father believed life without a calling was meaningless; it was therefore a race he expected to run until death stopped him.

Alzheimer’s was thus the cruelest way for him to die: the body still strong and capable but the mind dying — very slowly — from age sixty-five till its merciful end at age seventy-seven. It was OK for the first few years after his retirement: he still got up early, dressed professionally, and put in eight hours as a volunteer at a Christian mission organization — doing whatever was asked of him. But Karen later told me that the mission had kindly allowed my father to keep his office even though he was clearly unable to accomplish anything of value for them. She paid a small office rental fee, and they allowed him to keep his office and, temporarily, his sanity.

The first retirement crisis came when he got hopelessly lost one day on his half-mile walk back home. Frantically, Karen got in her car and drove around the neighborhood for over an hour before finding him, utterly confused, about two miles away from home. This became a regular occurrence, and soon his office days were over, and he began “working” at home.

But he would often wander around his house as if trying to escape from a maze,

plaintively asking no one in particular, “What can I do? There’s nothing to do!” Urging him to relax was as futile as rebuking a dog for barking when the doorbell rang. Duty was hardwired into him. “Just relax Pa!” I would urge again. “These are your golden years. Take it easy, read, do your gardening—don’t you have a hobby?”

But relaxing for my father just took too much effort. And I remembered that he had never had time for relaxing or hobbies. As an old-time Pentecostal, for whom the return of Christ was always imminent, hobbies were too frivolous when so much was at stake and so much hung between heaven and hell. His sense of duty thus compelled him to always be on the lookout for someone to help, something to pray about, someone to share the gospel with, some dishes to wash, some Bible to study. Even when watching TV with the family, he would often stand, as if ready to boltas soon as duty called. When he heard my mom’s car pull into the driveway from the grocery store, he would drop whatever he was doing and bolt out to help her. Whenever the doorbell rang, he would bolt out of his chair, bed, or shower and admit whatever guest was there. And whenever a lady entered a room, he would be the first to bolt up from his chair and offer it her. It was duty. And being off duty was anathema.

Thus began a new regimen for this duty-bound man. I watched as he slowly but doggedly stalked around the house doing his work: putting chairs on beds, clothes on dining-room tables, books in the kitchen sink, and silverware in the flower beds. And we, we stealthily followed behind, unobtrusively undoing his chaos. He never seemed to notice that his work had been undone, as he dutifully redid the work which we had just unraveled. Fortunately, he tired quickly, and we would persuade him to lie down and take a nap. But my father’s naps were never long. As exhausted as he might look, he would bounce out of bed five minutes later, often urgently announcing that he needed to get his work done. And then we would hear his plaintive mantra again: “There’s nothing to do!”

And this mantra was very different from the “I’m bored” mantra of a child, who expects you to find him something fun to do, and could be easily satisfied with some new game or toy. It expressed, I believe, a deep spiritual yearning to continue doing the work of the kingdom that his disease had deprived him of, a yearning to continue to obey Christ’s injunction to work diligently while it was still day, a yearning to hear Christ say, “Well done, thou good and faithful servant” (Matt. 25:21 KJV) on his return—a return which was always imminent in his Pentecostal theology.

***

A wonderful tradition I had when flying out to visit my dad in Pasadena was taking him for a walk, with my brother Garth, to Pronto Donuts, a hole-in-the-wall shop filled with retired Armenian men. He loved these times, but on August 7, 2010, we made our last such visit. He had started to experience “sunset panic” — a sudden desire to “go home” when the light begins to fade. He had just wolfed down his last doughnut. It was 8:00 p.m. And before my brother and I could stop him, he bolted for the door and headed into the heavy traffic on Hill Avenue, causing cars to screech to a halt. We dashed out to get him and quickly guided him back to the sidewalk. But he just as suddenly wrenched himself free of us and began stalking determinedly away, in the opposite direction of home. We attempted to coax him back, but he would have none of it. We allowed him to walk freely for a while before we had had enough and finally managed to manhandle him back in the right direction. When we arrived back home, he was exhausted, limping, and whimpering like a child. But on entering his front yard, he broke away from us again, indignantly shouting, “That’s not where I’m going!” And away he stalked again, in the opposite direction. When we finally managed to force him back home, he persistently tried to escape again, rattling the locked gate of his backyard persistently and emphatically. When he was finally exhausted, he sat down in a funk, as my brother and I coolly sat reading sections of the Los Angeles Times.

It was then that I noticed his chin quivering and his chest heaving in silent sobs. I went over to him, took his arm, and led him back inside. We sat together on the couch, and he began sharing with me his distress: “Oh God, Oh God, please help me! Please God! Please help me. I don’t know what to do. I want to go home! Please God, I want to go home!”

My father spent much of his last days wandering around his house from room to room, sometimes praying earnestly, sometimes whimpering sorrowfully, sometimes just humming to himself like a child trying to comfort himself when no one answers his cries in the night, and sometimes speaking in tongues. But one of his most common refrains was his cry for home. His world simply made no sense to him.

Alzheimer’s has often been described as a slow regression back to childhood, a stripping away in reverse chronological order of all the territorial skills we spent so long acquiring: locating food and comfort, recognizing, smiling, walking, talking, reasoning, bargaining, manipulating, loving, and building alliances. These are highly developed territorial skills that we have honed far above those of any other species. And when Alzheimer’s slowly strips these away, we once again become like infants, crying out in terror in a strange new world we can no longer control. We have forgotten how to mark our territory, and it bewilders and scares us.

One of the saddest yet funniest expressions of my father attempting to “mark his territory” was the day we were visiting the home of some relatives, and we suddenly heard a high-pitched scream coming from the living room adjacent to us. We all rushed into the room to find Pa standing over a beautiful white piano with his pants down around his ankles, peeing over the black and white keys. The poor lady of the house, who had screamed, was standing in the opposite corner, white and rigid in shock. He, of course, was quite oblivious to the horrifying scenario he had created—perhaps the white keys had reminded him of the porcelain in a bathroom, or perhaps some deeper territorial instinct had suddenly kicked in. Yet it remains one of the most poignant memories I have of my father, a sad yet hilarious reminder of how increasingly strange this world had become to him.

***

My father’s increasing weakness reminded me of the late Pope John Paul II during his final years: stricken with Parkinson’s disease, his hands trembling so badly he could no longer hold the host, his voice cracking, his mouth framed by drool , he still doggedly celebrated the Mass before millions at Saint Peter’s Basilica and via TV. “Why allow millions to see such frailty?” some would ask. “Why not pass this duty on to an abler bishop?” And I think he would have answered that there is no better duty than to celebrate our weakness in the Mass. I believe that this most public display of weakness captures the essence of Christianity as expressed in Saint Paul’s Epistle to the Philippians:

Have this mind among yourselves, which is yours in Christ Jesus, who, though he was in the form of God, did not count equality with God a thing to be grasped, but emptied himself, by taking the form of a servant, being born in the likeness of men. And being found in human form, he humbled himself by becoming obedient to the point of death, even death on a cross (2:5–8 ESV).

Just a few months before he died, I asked my father to say grace for us. He closed his eyes, furrowed his brow, and then, from his mouth, an avalanche of deeply earnest words began to flow, void of cognition yet filled with meaning: “Oh God, we, yes, ah Jesus, thank you Lord, we pray, oh God, yes, and in your name, oh God, and we praise you Father, in your name Jesus, we love you, and oh God, in Jesus’s name, amen!” As he prayed, his grip on my hand grew tighter and tighter until all the blood had been squeezed from my fingertips. And then, as he ended the prayer, he slowly released me. There was a rare look of peace on his face.

This last lesson, to accept his frailty, was perhaps the toughest lesson of all for my father. His resolute sense of duty, which had served him so well all his life, now seemed to be a terrible impediment to his peace.

Thomas Merton once wrote that “happiness consists in finding out precisely what the ‘one necessary’ thing may be, in our lives, and in gladly relinquishing all the rest.”5 I think my dad was often a Martha, frantically—and faithfully—serving God whenever and wherever possible. But he struggled in his last years to simply sit at Christ’s feet, like Mary, and enjoy his presence — the “one necessary thing.” Perhaps the “last necessary thing” for him (Luke 10:38–42).

But I could never convince him to become a Mary. His Martha — his frantic sense of duty — would eventually succumb to the ravages of Alzheimer’s in his final year. In my last two visits with him, he barely recognized me. But he seemed finally to have a reached a level of peace: still constantly moving, he would shuffle slowly from room to room like an old crab, singing softly to himself, praying in tongues, or having imaginary conversations. The outside world no longer seemed to perplex him. He would allow himself to be guided to a chair or the bed or the bathroom. He seemed to be in another world already. And finally he staggered and fell. Two days later he died, peacefully sleeping or mumbling while my brother and Karen kept vigil over him.

My most cherished memories of my father are those last three years, years in which I saw him struggle desperately against the dying of the light, years in which I saw a level of suffering I hope I will never have to experience. And yet it was in these years of suffering and disintegration that my father exerted his most profound influence upon me; it was an influence moreprofound than when he was at his greatest powers as a father, professor, or missionary. All his greatest virtues — dutifulness, tenacity, and fidelity — were showcased during these final years. As he weakened, his thrashings toward these virtues increased. As a mountain goat with a broken leg thrashes most desperately to regain its ability to gallop up steep mountain slopes, so my father thrashed most desperately to do his duty as his brain become more and more ensnared in the plaque and tangles of his dementia. Until finally he too lay still. But I had begun to see the awful weight of glory resting on him.

Two images capture my father’s weight of glory: his leathery face peering above a Bible that had long since begun to fade—his big fingers still traveling across every line of it—and an old picture I discovered of him baptizing hippies in the Indian Ocean during Cape Town’s hippie revival of the early 1970s. I don’t know which one I like more. In the former, I see the weight resting on him. In the latter, hesees the weight resting on others. Both are heavy.

- C. S. Lewis delivered what has become his most famous sermon at the University Church of Saint Mary the Virgin in Oxford, England, on June 8, 1941. See “The Weight of Glory,” in The Weight of Glory and Other Addresses (New York, NY: HarperCollins, 2001), 17; italics in original.

- See Swinton, Dementia: Living in the Memories of God (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 2012).

- See Keck, Forgetting Whose We Are: Alzheimer’s Disease and the Love of God(Nashville, TN: Abingdon, 1996).

- Edmarie Guzmán-Vélez, Justin S. Feinstein, and Daniel Tranel, “Feelings without Memory in Alzheimer’s Disease,” Cognitive and Behavioral Neurology 27, no. 3 (2014): 117–29.

- Merton, No Man is an Island (San Diego, CA: Harcourt Brace, 1955), 137.