“Success as theologians, pastors, and graduate students of theology must be secondary to the goal of loving God and neighbor, the weak and helpless of the land”—I encountered these words from James Cone as a first-semester graduate student at Union Theological Seminary in New York.1 They left an indelible impression on me. It is an impression I have sometimes been at odds to understand.

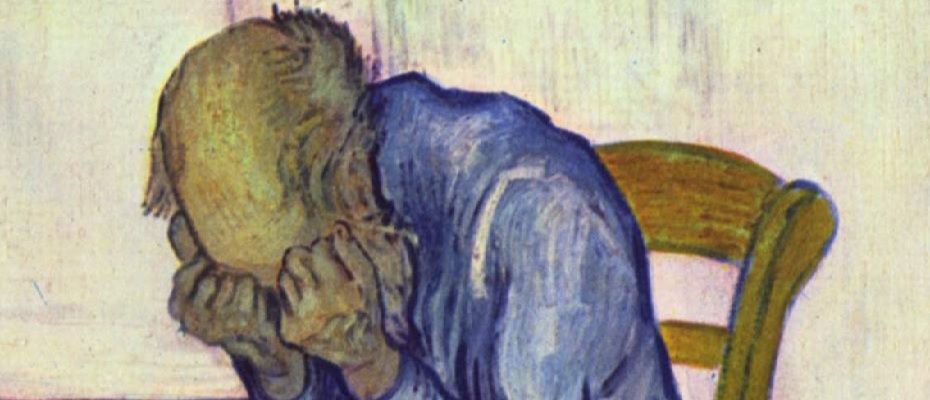

Later in the same speech, Cone expounded on Paul, noting that “God chose what was foolish in order to put shame to the world’s wise. What the world counts as base and despises, even the things that did not exist, God chose. Why? That God might do away with that which does exist.”2 This is a compelling theology for all of Christianity—it turns upside down the priorities of the world. The world loves power and exploitation. The world hates a loser. In Jesus, especially in Cone’s understanding, the world is shown the foolishness of brute power, and our hopes are carried with Jesus not to die on the cross but to survive beyond it and be transformed. This should be vindicating or comforting for the oppressed. It is, however, paradoxical for those of us who groan beneath the yoke of depression: when suffering from depression, we are among the base and despised, yet we are unable to feel the warmth of God’s preferential choice. When I feel that my own brain is trying to kill me, that my wife cannot possibly love me, or that my son will reject me when he is old enough to realize what a nonperson I truly am, there is little comfort in Cone’s words about God’s love for the lowly. Nevertheless, my experience of nonpersonhood—of nonbeing—has forced me to develop an empathetic connection to others. It has led me to an awareness of my kinship with the very people whom Cone speaks of as the “oppressed of the land.” Because of my depression, I now have a limited understanding of what it means to be told by white men that one is not a person worthy of consideration. I can begin to understand this because that is what I have been told by a white man, because that is what I have told myself.

***

The paradoxical message that emerges from Cone’s reflection strikes me hard when reading the words of Jesus. Take, for example, his words from the cross about self-denial. In Mark’s version, we have the following:

He called the crowd with his disciples, and said to them, “If any want to become my followers, let them deny themselves and take up their cross and follow me. For those who want to save their life will lose it, and those who lose their life for my sake, and for the sake of the gospel, will save it. For what will it profit them to gain the whole world and forfeit their life?’” (8:34–37 NRSV).

This passage, as well as its parallels in Luke and John, is often interpreted to mean that we must be willing to forgo luxuries and worldly approval in order to be genuine disciples of Christ. The crosses that we are to take up represent our individual burdens, which are often interpreted as the burden of our own past sins. In my depression, however, I read a very different suggestion in this text.

The cross isn’t something to be borne during my life—life is the cross. The act of being alive—breathing, eating, speaking with others—is a burden. I don’t want to save my life; my life is my cross. Even though I know that there is a world of difference between martyrdom and suicide, I find myself wondering whether Mark’s Jesus is letting me know that it might be OK to let go of that cross. After all, I suffer by living, and Jesus promises to end suffering, doesn’t he? This question suggests a somewhat unorthodox reading of these texts—a hermeneutics of suicide is not listed in theology textbooks or preached from the Sunday pulpit. Yet this theological perspective has marked my twenty-five-year struggle with major depressive disorder.

These days, ideas of suicide come and go, but thanks to the efforts of a good therapist and a good prescriber such thoughts are largely a nattering buzz, a nuisance. But this has not always been the case. Such thoughts have, in my recent past, been more insistent. They have been more plausible and credible than I like to admit. In the quiet hours of the day, there is an inaudible yet persistent voice that answers Jesus’s suggestion that I must hate life itself with “Yes, I do hate life. I hate it so much. Life itself is my cross. Let me lay it down, Lord. Please, let me lay it down.” I argue back against this urge. I resist. I rationalize. I take the pills. I go to the sessions. And then that internal monologue is quieter, but it’s still there. I doubt it will ever be silent.

When my depression is heightened and my internal struggle especially fraught, my hermeneutic of suicide dominates my encounters with Scripture. My studies in theology have taught me that Jesus’s sayings about self-denial are metaphorical and that church teaching is strikingly consistent in its criticism of suicide, yet these facts don’t easily loosen the existential hold of suicidal thinking on my psyche. And so, rather than dismissing the scriptural interpretations that have arisen from suicidal thinking, I have found that they can illuminate otherwise overlooked truths in Scripture that have profoundly affected my Christian life for the better.

Consider, for instance, the story of the Gerasene demoniac, a healing/exorcism story with a strong thematic connection to mental illness:

They came to the other side of the sea, to the country of the Gerasenes. And when he had stepped out of the boat, immediately a man out of the tombs with an unclean spirit met him. He lived among the tombs; and no one could restrain him any more, even with a chain; for he had often been restrained with shackles and chains, but the chains he wrenched apart, and the shackles he broke in pieces; and no one had the strength to subdue him. Night and day among the tombs and on the mountains he was always howling and bruising himself with stones. When he saw Jesus from a distance, he ran and bowed down before him; and he shouted at the top of his voice, “What have you to do with me, Jesus, Son of the Most High God? I adjure you by your God, do not torment me.” For he had said to him “Come out of the man, you unclean spirit!” Then Jesus asked him “What is your name?” He replied “My name is Legion; for we are many.” (Mark 5:1–9)

R. S. Sugirtharajah considers this passage from the context of postcolonialism, noting the colonized context from which the authors of Mark approach the text. From this perspective, he treats “the action of Jesus as neutering the only option the oppressed people had in declaring their opposition to the colonial occupation.”3 For Sugurtharajah, feigning “madness,” or even legitimately succumbing to it as an effect of posttraumatic stress disorder, was and is a method of nonviolent resistance to a colonial oppressor. The demoniac is noted for his strength—neither chains nor shackles could hold him—and likely would have been conscripted into the Roman legions. By removing the demons, Sugurtharajah suggests, Jesus may have prevented this man from resisting his oppressor.

Depression has often positioned me in the place of the demoniac, filled with the “unclean spirits” of depressive and suicidal thoughts. In this state, I’ve wondered, as Sugurtharajah does, whether it would be better to have my tormenting spirits driven off a cliff or to live in the tombs as an outcast. I am frighteningly uncertain about whether the exorcism of my depression would be good or bad. There are days that I wish for those spirits to be gone, and there are days that I feel so bound to something I know to be toxic that I cannot imagine myself without this illness. There is, in other words, a kind of ontological codependence between the healed person I wish to be and the unhealable wretch I fear that I actually am. The tension implicit in this relationship determines my reading, not only for the fifth chapter of Mark but also more broadly for theology as a discipline.

Indeed, my depression has shaped my work as a theologian with insights that I would not possess were I miraculously healed of this condition. First, depression offers me an empathetic point of entry to understanding black experience, especially in the work of James Cone, whose work is central to my own. To be sure, I do not intend to suggest equivalence between my suffering as a white man with depression and the suffering of a black woman or man who struggles to have her or his humanity recognized. They are not the same thing. Depression or no, I still receive the benefits of whiteness in a society that tilts toward unjust idolatry of the white body.

Yet I still see myself reflected in the writing of Cone. In his memoir My Soul Looks Back, Cone recounts the following about his boyhood community: “God was that reality to which the people turned for identity and worth because the existing social, political, and economic structures said that they were nobody.”4 I am a beneficiary of those same social, political, and economic structures that told the black citizens of Bearden, Arkansas, they were nobody. Yet I also struggle daily with an internal narrator who tells me that I am nobody. In other words, I find it easy to believe that black people can be held down by the white man saying they are worthless because I also have a white man telling me I am worthless, because I also feel the weight and difficulty of rising up from under that ever-present critique. I do not have access to the internal life of someone like Cone, a black man raised in the apartheid South, but I can understand the horrible tension that arises between a religious life that says “you are valued and cherished” and a world that says “you are worthless and disposable.” I can appreciate with the oppressed that the latter statement is a distortion of reality while also understanding that the affective impact of that statement is not dulled merely by recognizing it as false.

In the 1970 foreword to A Black Theology of Liberation, Cone states that,

There will be no peace in America until whites begin to hate their whiteness, asking from the depths of their being: “How can we become black?”. . . But until then, it is the task of the Christian theologian to do theology in the light of the concreteness of human oppression as expressed in color, and to interpret for the oppressed the meaning of God’s liberation in their community.5

Cone’s call to hate my whiteness gives structure to Jesus’s declaration that unless I hate life itself, I cannot be a disciple. Cone does not mean that we must hate our white skin or our white bodies but that we should hate the oppression and exclusion they have come to signify in our society; we should hate the sociopolitical framework that values the supremacy of one skin color above all others.

Cone offers me a framework that can counter the suicidal hatred of life-as-continued-metabolism which I might otherwise hear in Jesus’s words. It is not living that is detestable and must end. It is living as white. It is accepting unearned privilege as valid and deserved. It is my passive continuation of a system of white supremacy that values my life and my being more than Cone’s simply because of the accidents of our biographies.

The experience of depression and suicidal thinking has thus left me with an opening to experience something of the tension Cone discusses, to experience something of a society that says no to what God, in Jesus, affirms, namely, our own worth and humanity. Contrary to Cone’s context of external political and social struggle, this is an internal struggle on my part. Nobody else is telling me that I am unworthy of God’s love. I’m left in a state of uneasy worry. I question God’s wisdom and knowledge, asking, “How can God believe that I am a person worthy of existence and salvation, when I know in my bones that this is not the case?” There is no easy answer, but I do know that this worry and doubt shape my theological context. I read healing stories of the Gospels and wonder what “healing” really means. I can empathize, even slightly, with the lament of Cone’s theology. Perhaps I can speak to others in my sociopolitical context to let them know: James Cone is right. Jesus doesn’t need white Christians.

In this way, my depression has connected me to larger interests of justice and community. Depression affords me a connection to the contexts of Sugirtharajah and Cone, which in turn help me see more to the sayings of Jesus that we’ve already examined. Their readings then add new dimension to my depressive hermeneutic. When I view myself as the demoniac and Legion as the internalized structures of whiteness, I can fully agree that the racist bias that takes hold of me should be cast into a herd of swine or into the sea. This is a justice-oriented identification with the text that my suicidal hermeneutic alone cannot afford. According to this reading, Jesus does not heal me as just one individual. The exorcism of white supremacy must unfold as a communal healing.

But I must also attend to Sugirtharajah’s less-charitable reading of the story. It is still possible that the presence of Jesus can be used to pacify troublemakers and bend resisters to the will of an oppressive social regime. One needn’t look further than the white TV evangelists and megachurches or practitioners of the so-called prosperity gospel to see how this might work out. The Jesus who calls us to fellowship too soon is the one who can reply “All Lives Matter” to the calls that “Black Lives Matter.” Christians who follow the Jesus who calls for unity above all can overlook the dangers faced by marginalized people under Donald Trump’s presidency, assenting to a cynical call to unity that demands no sacrifice on their part. Whatever else Jesus does in the Gospels, he calls us to change. All Christians struggle to determine what Christian transformation looks like. This is particularly tricky for me because the voices in my head that exhort me to self-harm are the same ones that have helped me to empathize with my neighbor.

In light of all this, my identity as a white male theologian living with depression is shaped by the tension I’ve described here. I am told that my condition—this depression—is a medical condition; that it is biological. It is in some sense as inescapable as my own skin, and it leads me to doubt whether my very being is something Jesus wants. And yet, in the despair born of such doubt, I encounter the truth of Scripture in new ways, and they in turn, nurture empathy and compassion with those who suffer most under our racist regime. Through my depression, I realize that my liberation is bound up with the liberation of the oppressed.

The paradox of my depression calls to mind the old children’s hymn “I’ll Be a Sunbeam,” with lyrics by Nellie Talbot that state, “Jesus wants me for a sunbeam / To shine for him each day / In every way try to please him/ At home, at school, at play.” That’s a fine message for children perhaps, but the Scottish band the Vaselines have their own take on this song, one that begins, “Jesus don’t want me for a sunbeam / ’Cause sunbeams are not made like me.” That version rings true to me. I wasn’t made to be a sunbeam, and this has made all the difference for me as a Christian and theologian.

- James Cone, “The Vocation of a Theologian,” Union News (Winter 1991): 4.

- Ibid.

- Sugirtharajah, Postcolonial Criticism and Biblical Interpretation (New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2002), 94.

- Cone, My Soul Looks Back (Maryknoll, NY: Orbis, 1986), 23.

- Cone, A Black Theology of Liberation, 20th Anniversary Edition (Maryknoll, NY: Orbis, 1986), v–vi.